Why The Powerful Countries Rushing Back To The Moon

It’s been over 50 years since the United States sent the first humans to the moon, in what was a highly competitive space race between the U.S. and the former USSR. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard. Now there’s a renewed interest to return to the moon with many more global players involved. Russia launched its first moon landing spacecraft in nearly 50 years. India has become the first country to reach the south pole of the moon, and the fourth country to ever land on the moon. China sent its youngest ever crew to its orbiting space station today, as the country reiterated plans to put astronauts on the moon by the end of the decade.

U.S. Lunar Lunar Lander

This morning, history is being made. The first U.S. Lunar lander in more than 50 years is on its way to the moon’s surface. Japan has made history as the fifth nation to successfully land on the moon. There’s renewed interest in the moon. We’re going back to learn to live in a deep space environment for long periods of time, so that we can go to Mars and return safely. The moon is a proving ground. We need to get to the moon. Humanity needs to get to the moon in order to learn how to live in space. In order to learn how to utilize the resources of space and that is really the stepping stone to all of the vast riches in the universe. And who gets to the moon this time around could have implications on Earth as well as the cosmos. Whoever gets to establish a significant lunar presence is making a statement about their political system, about their economic system, about who is ahead in the geopolitical competition. But a second, newer part to this is the belief that there are significant resources on the moon that are useful to Earth or are useful for future spaceflight.

First Country On The Moon

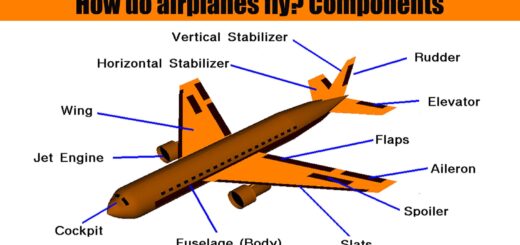

The United States was the first country to put man on the moon in 1969, and to this day is still the only nation to have landed people on the moon. In 1959, the Soviet Union beat the U.S. To become the first nation to reach the surface of the moon with its Luna 2 spacecraft. This all happened during the peak of the Cold War. That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind. Spacecraft sent to the moon are typically categorized into several mission types. A flyby mission passes close to the moon, but does not go into orbit around the moon. Think of it as an initial reconnaissance mission. An orbiter mission allows the spacecraft to go around the moon continually taking detailed photos or radar images of it.

A hard- landing mission is where a probe crashes into the moon. Those can be intentional, with the impact kicking up debris that can then be analyzed, often by the instruments of an orbiter spacecraft, or unintentional when an attempted soft landing goes awry. Soft landings are typically the most challenging and costly missions, as the spacecraft must make it to the surface of the moon with its structure and instruments fully intact. Since the late 1960s, there’s been over 20 successful soft landings on the moon. Six of those were NASA’s manned Apollo missions, and globally, more than 100 lunar missions are expected to take place by 2030.

A major reason for this renewed interest in going back to the moon was finding concrete evidence of a valuable natural resource, water. For years following the Apollo missions, scientists had seen clues of water on the moon. But it wasn’t until India’s Chandrayaan-1 mission, which sent an orbiter and impactor to the moon in 2008, that researchers became confident that the moon was not as dry as they originally thought. When we thought that the moon was really just sort of barren and had nothing, the concept of sending somebody to the moon and trying to keep that person alive was just colossally expensive, and there didn’t seem to be a benefit. But now we have water so we can send people to the moon, and we can support them on the moon without having to send water up.

The altitude is being brought down from 800m, and we are nearing and approaching the lunar surface. In August of 2023, India made another breakthrough, becoming the first nation to successfully soft land on the moon’s south pole, an area that scientists think is the most likely to contain large reserves of water. Earlier that month, a Russian probe en route to soft land in the same area crashed into the moon after it spun into an uncontrolled orbit. We’re pretty sure there is water on the moon. We’re pretty sure that most of it is in these very, very deep craters on the lunar south pole because no sunlight ever gets to them. Aside from being crucial for human survival, water can be used to make rocket fuel by splitting its components, oxygen and hydrogen, and liquefying them.

When these two elements are brought back together, the chemical reaction results in a burst of energy that can be used to propel a rocket. NASA is using this fuel type in its new SLS rocket that will launch astronauts back to the moon. With access to water, the moon could one day become a refueling station for rockets and a springboard for deeper space exploration. Private companies and countries are also eager to mine the moon for rare-earth metals. And then there’s the isotope helium-3, which, while rare on Earth, is abundant on the moon and can theoretically be used to power nuclear fusion reactors. We haven’t figured out quite how to do it yet. There’s a lot of theories about it, but once we figure that out, the helium-3 on the moon could seriously power the Earth.

The entire Earth for centuries

The presence of water on the moon and access to its other resources have motivated a number of nations and commercial companies to explore it. In the last few years, Japan, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, and India have all sent spacecraft to the moon with varying degrees of success. Most recently, Japan became just the fifth nation to soft land a spacecraft on the moon. On the heels of its own successful unmanned moon landing, India has also said that it plans to put an astronaut on the moon by 2040. Russia two has expressed a desire to put astronauts, known as cosmonauts, in Russian, on the moon between 2031 and 2040, according to state-owned media.

But the biggest competition is between the United States and China, and who can set up a presence on the moon first. Once you have a human presence, you start establishing rules. That’s just human nature. And really the question then becomes, what will be the lingua franca? What will be the common language of lunar exploration? Will be English, or will it be Chinese? The U.S. Effort to return to the moon is known as Artemis. The program is spearheaded by NASA in conjunction with a number of commercial and international partners, and is expected to cost the country over $93 billion through 2025. Artemis is all about getting people back to the moon for long duration, so eventually we want to get people on the surface of the moon for up to 30 days and it’s first about science. We want to understand the south pole of the moon, which is where we’re flying to and we also want to test our systems close to home in a partial gravity environment before we send crews on to Mars.

As has become the norm, NASA is working with a number of commercial partners to build out its Artemis infrastructure. Some of these companies include Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Aerojet Rocketdyne, Northrop Grumman, Blue Origin, SpaceX, Axiom Space, and Collins Aerospace. NASA’s first mission, Artemis I, took place in 2022 and tested NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft, which will eventually carry astronauts to lunar orbit. More recently, NASA, in partnership with commercial company Astrobotic, launched the country’s first lunar lander in decades, though it suffered a technical anomaly shortly after launch. The Artemis II mission, which was originally scheduled for November 2024 but has since been pushed back to September 2025, will launch four astronauts into orbit around the moon before Artemis III returns astronauts to the moon’s surface in September 2026.

Flying back to the moon is very hard, and getting to the south pole is even harder creating deep space systems to function for 21 days in orbit, 30 days on the surface, it takes time to prove that out. As part of its Artemis objectives, NASA is working to build a space station that will orbit the moon, as well as establish a base camp on the moon’s surface. We’ve talked about setting up something called the Lunar Gateway Station, so that would be a space station that would in fact, be manned all the time, that would orbit the moon. And every so often you would then see a crew go from the Lunar Gateway station to the lunar surface, where they presumably would have shelters and habitats and things like that. Meanwhile, China is a relative newcomer to the space race, with the country not having conducted a manned spaceflight until 2003. But China has since made tremendous progress.

The country built its own earth orbiting station after Congress banned all scientific collaboration between NASA and China in 2011, meaning China lost access to the International Space Station. Along with a number of partners including Russia, Venezuela and Pakistan, China has also announced plans to build its own research station on the lunar surface, and has said it wants to put astronauts on the moon by around 2030. United States’ aerospace leadership has expressed concerns about China’s moon ambitions, especially if the country were to establish a presence on the moon before the U.S. I think the space race is really between us and China, and we need to protect the interests of the international community. You see the actions of the Chinese government on earth.

They go out and claim some international islands in the South China Sea, and then they claim them as theirs. So naturally, I don’t want China to get to the South Pole first with humans and then say, this is ours, stay out. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 is often seen as the cornerstone of international space law. Over 100 countries, including the U.S., Russia and China, are party to the legally binding treaty, which details the rules governing the peaceful exploration and use of space. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 said, nobody can own a planet. Nobody can own a natural satellite, the moon, any of the moons of Jupiter or something like that. It said that you cannot deploy weapons of mass destruction. But parts of the Outer Space Treaty can be vague and left up to interpretation.

President Obama in 2015 signed a law that said, we interpret article two, which is that article that says you can’t claim territory in space to mean that you can extract resources and that’s not claiming territory. So once you take the resources off that other celestial body, they are yours. They are your property at that point. Article nine of the Outer Space Treaty, which says that nations should conduct activities, quote, with due regard to the interests of other nations, has also been ambiguous. We don’t know exactly what due regard means.

The United States has said, well, we think due regard means that you have to respect an exclusionary zone or a coordination zone around any operations or any objects that we have in space. It’s not difficult to imagine such an exclusionary zone being set up by a country around a place rich in natural resources, for example. If you get to some of the most water-rich areas first, you could, because there is no formal legal system here, try to lay claim to that. If that first mover also is the first mover with respect to fusion, that first mover is going to control not just the moon, but the earth as well, because they will have the access and be able to distribute that helium-3.

In addition to the Outer Space Treaty, coalitions of different nations have come up with their own sets of rules. In 2020, the United States introduced the Artemis Accords. This is a non-binding multilateral arrangement between the United States government and the over 30 other world governments participating alongside the U.S. In the Artemis program. Notably missing from these signatories, however, are China and Russia. Russia and China objected to the Artemis Accords for two reasons. Russia, of course this was during Covid, just prior to the invasion of Ukraine, said, oh, this is the United States being imperialist. We’re gonna have none of it. And China has said, we’re not going to look at the Artemis Accords because they were negotiated outside of the United Nations, which is the only place where space law should be made. But even if everyone on earth was to agree on a set of laws for outer space, enforcement right now would be another issue.

Enforcement of international law

We we know that we don’t do a good job of that here on earth. Imagine a violation of international law in space, and we can’t even send people to the moon right now. And so enforcement is going to be very difficult. But before any nation can establish a presence on the moon or claim its riches, they have to overcome some tough challenges. For China, the big challenges are this is brand new and they are still developing some of the key technologies associated. For example, a heavy lift booster to lift the space capsule and crew and consumables that would be necessary not only to go to the moon, but obviously to bring them back. The challenge to us is very, actually very basic. The Chinese approach is one based on longterm planning with programmatic stability.

We have had repeated studies and projects and exploratory commissions on not only going back to the moon, but also going to Mars. But budgets change every 4 to 8 years depending on who the president is, even more frequently if you think about who runs Congress. One of the things that was really phenomenal about the transition from Trump is that we did not lose Artemis. It was like the one thing that the Biden administration kept from the Trump administration. But despite the challenges facing individual countries, as they continued to push the boundaries of what we can do in space, Hanlon remains optimistic.

The exploration and use of space by treaty, by the Outer Space Treaty, is supposed to be for the benefit of all and we can make it that way. Competition isn’t necessarily a bad thing. We need to have a lot of countries excited because this is our first step as a human race versus as a Chinese person, an American person, a British person, a Kenyan person. Right? We need to stop thinking about ourselves in that way. And space is the way we’re going to do that.