Integrated Circuit

An integrated circuit (IC), sometimes called a chip, microchip or microelectronic circuit, is a semiconductor wafer on which thousands or millions of tiny resistors, capacitors, diodes and transistors are fabricated. An IC can function as an amplifier, oscillator, timer, counter, logic gate, computer memory, microcontroller or microprocessor.

An IC is the fundamental building block of all modern electronic devices. As the name suggests, it’s an integrated system of multiple miniaturized and interconnected components embedded into a thin substrate of semiconductor material (usually silicon crystal).

A single IC could contain thousands or millions of:

- transistors

- resistors

- capacitors

- diodes

Additional components may also reside on it, all interconnected through a complex web of semiconductor wafers, silicon, copper and other materials. Size-wise, each component is small, usually microscopic. The resulting circuit, a monolithic chip, is also tiny — often just enough to occupy a few square millimeters or centimeters of space.

One common example of a modern-day IC is the computer processor, which typically contains millions or billions of transistors, capacitors, logic gates, etc., connected together to form a complex digital circuit. Although the processor is an IC, not all ICs are processors.

History and evolution of integrated circuits

The invention of the transistor — a combination of the words transfer and resistor — in 1947 set the stage for the modern computer age.

In the early days, each transistor came in a separate plastic package, and each circuit consisted of discrete transistors, capacitors and resistors. Due to the large size of these components, early ICs were only capable of holding a few of them — wired together — on the circuit board.

Over time, the development of solid-state electronics made it easier to reduce the size of components.

In the late 1950s, inventors Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments, Inc., and Robert Noyce of Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation found ways to lay thin paths of metal on devices and have them function as wires. Their solution to the problem of wiring between small electrical devices was the beginning of the development of the modern IC.

Modern integrated circuits

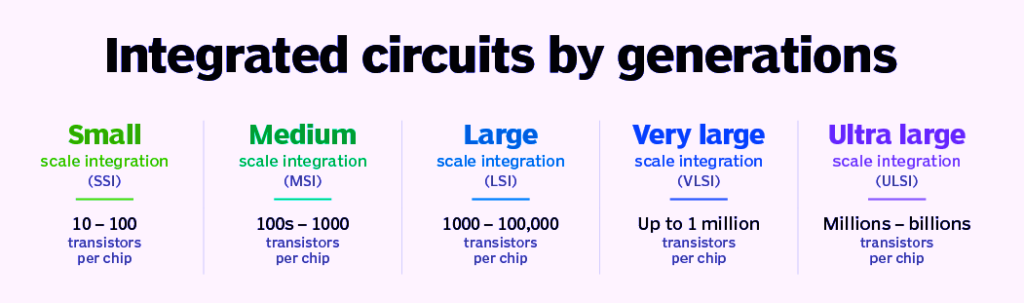

For the past half-century, ICs have progressed enormously with faster speeds, greater capacity and smaller sizes.

Compared to the early days, today’s ICs are unbelievably complex, capable of holding billions of transistors and other components on a single small piece of material. The modern IC is all one piece, with individual components embedded directly into the silicon crystal, rather than simply mounted on it.

An IC relies on multiple levels of abstraction. The semiconductor wafer that makes up the IC is fragile and contains numerous intricate connections between its many layers. A combination of these wafers is known as a die.

With millions or billions of components on one single chip, it’s not possible to position and connect each component individually. Dies are too small to solder and connect to. Instead, designers use a special-purpose programming language to create small circuit elements and combine them to progressively increase the size and density of components on the chip to meet application requirements.

The ICs are “packaged” to turn the delicate and tiny die into a black chip that now forms the basis of hundreds of devices, including:

- computers

- mobile phones and smartphones

- cars and airplanes

- amplifiers

- network switches

- other electronic devices: washing machines, toasters, microwaves, televisions, etc.

Types of integrated circuits

ICs can be linear (analog), digital or some combination of the two, depending on their intended application.

Analog or linear ICs have a continuously variable output, depending on the input signal level. In theory, such ICs can attain an infinite number of states. With this IC type, the output signal level is a linear function of the input signal level. Ideally, when the instantaneous output is graphed against the instantaneous input, the plot appears as a straight line.

Linear ICs are used as audio-frequency (AF) and radio-frequency (RF) amplifiers. The operational amplifier (op amp) is a common device in these applications. Another common application of an analog IC is the temperature sensor. Linear ICs can be programmed to turn various devices on or off once a signal reaches a particular value. These include:

- air conditioners

- heaters

- Ovens

Unlike analog ICs, digital ICs don’t operate over a continuous range of signal amplitudes. Rather, they operate at only a few defined (discrete) levels or states. The fundamental building blocks of digital ICs are logic gates, which work with binary data, i.e. signals that have only two different states, called low (logic 0) and high (logic 1).

Digital ICs are now used in an increasing number of applications, including:

- computers

- enterprise networks

- modems

- frequency counters

A mixed IC incorporates both analog and digital design principles. It may function as a:

- digital-to-analog converter

- analog-to-digital converter

- clock/timer IC

Microprocessors and ICs

The microprocessor is the most complicated type of IC, capable of performing billions of operations per second. In a computing device, a microprocessor contains the central processing unit (CPU) which runs a computer or the graphics processing unit (GPU), which specializes in the rendering images and video. A single microprocessor contains billions of interconnected transistors, each of which performs a specific logic function based on instructions from the clock.

When the clock changes state, the transistors perform the logic functions (e.g., calculations) they are programmed to perform. The clock’s frequency determines the speeds of these functions.