How Does GPS work?

Summary

To put it simply, GPS is a system that has three basic parts: satellites, ground stations, and receivers. Grounds stations use radars to find out if the satellites really are where they’re supposed to be. The GPS system has 32 active satellites orbiting the Earth. 24 of them are core satellites, and the rest serve as emergency replacements when something happens to the others. A receiver on Earth has to see at least 4 satellites to calculate an accurate location because the GPS uses a trilateration mechanism. 2-D trilateration is about calculating its latitude and longitude position on a map. When it comes to 3-D trilateration, it’s basically the same, but there’ll be spheres instead of circles on your drawing. 3-D position includes your latitude, longitude, and altitude. GPS satellites send information about their position and current time to a GPS receiver at certain intervals. The receiver gets the information in the form of a signal. GPS satellites have atomic clocks that keep the most precise time, but it would be impossible to install these clocks in every receiver. Satellites’ atomic clocks get 38 microseconds ahead of ground clocks every day. If scientists did nothing about it, GPS locations would be off by 6 miles more every day. There’s also a GPS almanac in the receiver that keeps track of where this or that satellite should be at any moment. GPS not only determines the most accurate location of people and objects, but also sends time signals that are accurate within 10 billionths of a second. Even though it’s incredibly accurate and useful, sometimes GPS takes people to unexpected places, especially in rural areas. Once upon a time, your ancestors used to look at the night sky to determine their location.

Then we used a Thomas Guide, remember those? Today, it only takes one magical technology to get driving directions, send your picnic spot to a lost friend, or track how far you’ve gone during a workout that technology is called GPS, and you’re about to find out the secret behind it.

GPS Stands for?

GPS stands for Global Positioning System, and was actually a military invention. Its first name was Navstar, and the first satellite was launched in 1978. But not all the Navstar satellites made it to orbit, so it was still a work in progress. GPS became fully functional in the US by 1995, and was first used in cars in 1996. The highest quality signals were only used for military purposes until May 2000, when it became available to all civilians for free. Today, GPS is managed by the US Air Force. Many modern receivers actually rely on both GPS and the Russian GLONASS satellites to make their accuracy perfect anywhere in the world. GPS doesn’t need an Internet connection or a phone signal to function properly; but with them, it becomes more effective. GPS is literally everywhere, and you can now even purchase GPS insoles to keep track of your kids or relatives with Alzheimer’s disease.

How does it work?

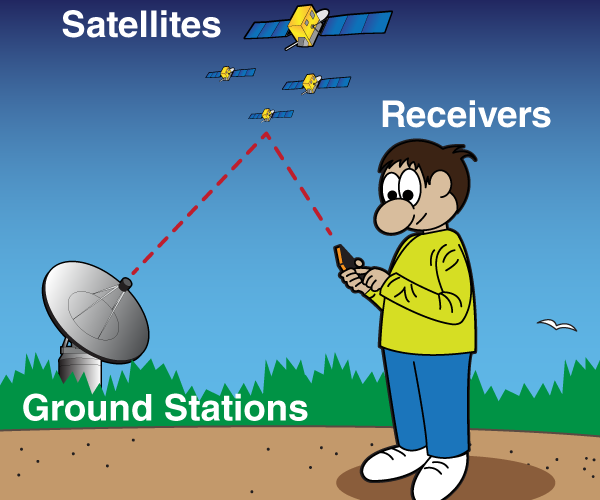

To put it simply, GPS is a system that has three basic parts: satellites, ground stations, and receivers.

Satellites today are like the stars and constellations that our ancestors used to find out their location. They’re supposed to be in a certain place at a certain time, and this is important.

Grounds stations use radars to find out if the satellites really are where they’re supposed to be.

A receiver in your phone or in your car is following signals from the satellites to determine how far it is from them. When it finds out how far you are from four or more GPS satellites, it can tell exactly where you are, with accuracy within feet or even inches!

The GPS system has 32 active satellites orbiting the Earth, 24 of them are core satellites, and the rest serve as emergency replacements when something happens to the others. They need constant maintenance and sometimes repairs, but even with all that, they only last about 10 years.

GPS works in any weather, rain or shine; but there is one important condition. A receiver on Earth has to see at least 4 satellites to calculate an accurate location because the GPS uses a trilateration mechanism. No worries folks, it sounds complicated, but I’ll explain it in a second! 2-D and 3-D trilateration So, 2-D trilateration is about calculating its latitude and longitude position on a map.

Imagine you went for a run Forrest Gump style, left your home in, say, Wisconsin, and made your first stop after days of running. You know you’re still in the US, but since GPS doesn’t exist yet, you have no clue where exactly you are. So luckily, you run into a farmer and ask him. He doesn’t answer directly, but gives you the first clue. You’re 400 miles away from Boise, Idaho. Well, that’s not really helpful because there are hundreds of places that fit that description. So you need more clues and ask another person. They kindly inform you that you’re 780 miles from Fargo, North Dakota. If you put this information you have on paper and draw two circles, you’ll see they only intersect at certain points. And now you know you’re in one of them! Still, that’s not enough and you find a friendly girl-scout who tells you the final clue.

You’re 410 miles away from Salt LakeCity, Utah! That’s all you need to know. As you add the third circle to your drawing, you see only one intersection point. Bingo! All this data helped you figure out you’re in Boseman, Montana! Which is a nice town! That’s all pretty simple, right? When it comes to 3-D trilateration, it’s basically the same, but there’ll be spheres instead of circles on your drawing. 3-D position includes your latitude, longitude, and altitude. If the radii from the previous example went in all directions, you’d get a series of 3-D spheres. So if you know you’re 15 miles away from satellite A, then you’re at some point inside an imaginary sphere that has a 15-mile radius. You’re also positive you’re 20 miles away from satellite B. When two spheres overlap, you’ll see a circle. Take the distance from the third satellite to build another sphere, and you’ll get two points of intersection.

Let’s take the Earth itself for the fourth sphere, because you know you’re on the ground and only one of the two possible points is the one you need. The more satellites you use, the more accurate position you’ll get. Doing the calculations GPS satellites send information about their position and current time to a GPS receiver at certain intervals. The receiver gets the information in the form of a signal. The GPS receiver analyzes radio signals from the GPS satellites to figure out two important things: the location of at least three satellites in space above you, and the distance between you and those satellites. Radio waves travel at the speed of light. The receiver takes the time it took for the signal to travel from space to the Earth to calculate how far it’s traveled. And it’s not so simple.

GPS Satellites

GPS satellites have atomic clocks that keep the most precise time, but it would be impossible to install these clocks in every receiver. They cost somewhere between $50,000 and $100,000, so it would make your phone really, really expensive. So, receivers have regular quartz clocks in them that keep updating themselves to get the most precise time, thanks to the information they receive from satellites. The second complication is that time moves faster for objects that are far away from gravity; like Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Satellites’ atomic clocks get 38 microseconds ahead of ground clocks every day. If scientists did nothing about it, GPS locations would be off by 6 miles more every day using at least four, and not three satellites helps to solve both of the problems and to determine the precise locations of objects. When you use just three satellites and three spheres, they’ll intersect at some point, even if you’ve got the wrong numbers. When you have four spheres, there’s no chance you’ll get the wrong measurements. One more thing, it’s not only important to know how far the satellite is from the receiver, but where exactly the satellite is. This task isn’t that hard, in fact, because satellites have predictable orbits.

There’s also a GPS almanac in the receiver that keeps track of where this or that satellite should be at any moment. The pull of the moon and the sun affect the orbits just a bit, but the Department of Defense takes care of that and sends updated information to all GPS receivers, along with satellites’ signals. GPS not only determines the most accurate location of people and objects, but also sends time signals that are accurate within 10 billionths of a second. You can only get more accurate time from the atomic clock, like the one in the GPS satellites. Banking systems, power grids, and cellular networks all rely on GPS for operations from synchronized call handoffs to accurately timestamped transactions. And here’s a Bonus Even though it’s incredibly accurate and useful, sometimes GPS takes people to unexpected places, especially in rural areas.

Ever get lost? Me too. It can be hard for it to tell an actual road from a mud path, and the consequences are pretty unpleasant for the driver and the passengers. A van driver from Switzerland, for example, once found himself on top of mount Bergun. He was unable to go either back or forward, and so he had to call for help and a heavy lifting helicopter eventually saved him. He explained to his rescuers that GPS prompted him to get off the main road and he couldn’t ever get back even when he wanted to. Three ladies in Bellevue, Washington didn’t have time to wait for a helicopter but had to leave their sinking Mercedes-Benz SUV behind. They were driving after midnight and couldn’t see that the road GPS told them to take was actually a boat launch that took them directly into the lake! Another story took place in Australia, where three Japanese students were trying to get to North Stradbroke Island by car. Their GPS suggested a route that ignored one detail – there was water and mud separating the island from the continent that looked okay to them at low tide. They were rescued by a truck driver. Hey technology is great – when it works.