History of Christmas Day Celebration

INTRODUCTION:-

Christmas, observed on the 25th of December, is a significant religious holiday and a widespread cultural and commercial event. It is celebrated globally with a blend of religious and secular traditions that have been cherished for centuries.

For Christians, Christmas is a joyous occasion commemorating the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, a revered spiritual leader whose teachings are fundamental to their faith. The festivities involve a myriad of customs, such as the exchange of gifts, the adornment of Christmas trees, attending church services, enjoying festive meals with loved ones, and the excitement of anticipating Santa Claus’s visit.

Since 1870, December 25th has been recognized as a federal holiday in the United States, allowing people nationwide to come together and celebrate the spirit of Christmas. The day holds significance not only for its religious roots but also as a time for unity, generosity, and the warmth of shared traditions.

When Was Christmas start?

The origins of Christmas trace back to ancient times, evolving from various winter celebrations observed centuries before the advent of Jesus. Even before the arrival of Christianity, people across the world commemorated light and life during the mid-winter season.

Centuries before the common era, early Europeans, including the Norse in Scandinavia, marked the winter solstice, typically around December 21. This celebration, known as Yule, extended through January. To honor the return of the sun and the promise of longer days, families would bring home substantial logs, igniting them in a festive display. The revelry continued until the log burned out, often spanning up to 12 days. According to Norse beliefs, each spark from the fire symbolized the birth of a new pig or calf in the upcoming year.

In various parts of Europe, the end of December offered a fitting time for merriment. With most cattle slaughtered to avoid winter feeding responsibilities, fresh meat became readily available during this season. Additionally, the fermented wine and beer produced throughout the year finally reached maturity, adding to the reasons for celebration.

In Germanic traditions, the mid-winter holiday involved appeasing the pagan god Odin. Fearful of Odin’s supposed nocturnal flights, during which he observed people and determined their fates, many chose to stay indoors to avoid his gaze. These diverse cultural practices set the stage for the eventual development of Christmas into the widely celebrated and culturally rich holiday we recognize today.

Saturnalia and Christmas

In certain regions of Europe where winters were milder than the harsh conditions in the far north, there existed a celebration known as Saturnalia, dedicated to honoring Saturn, the god of agriculture.

Beginning in the week leading up to the winter solstice and extending for a full month, Saturnalia was a festive period marked by indulgence, with abundant food and drink. During this time, the traditional Roman social hierarchy was upended, and for a month, enslaved individuals were granted temporary freedom and treated as equals. Businesses and schools closed their doors, allowing everyone to partake in the revelry of the holiday.

Additionally, around the winter solstice, Romans observed Juvenalia, a feast dedicated to celebrating the youth of Rome.

Simultaneously, members of the upper classes often commemorated the birth of Mithra, the god of the unconquerable sun, on December 25. Legend held that Mithra, an infant god, emerged from a rock. For certain Romans, Mithra’s birthday held particular significance as the most sacred day of the year. These diverse festivities and observances laid the groundwork for the eventual convergence of traditions, contributing to the rich tapestry of customs associated with the modern celebration of Christmas.

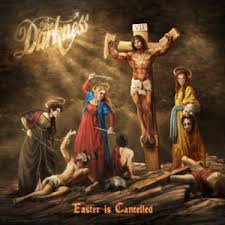

When Christmas was cancelled

In the early 17th century, a wave of religious reform reshaped the way Christmas was observed in Europe. When Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan forces seized control of England in 1645, they made a commitment to eliminate perceived decadence, leading to the cancellation of Christmas. However, due to public demand, Charles II was reinstated to the throne, ushering in the revival of this beloved holiday.

The Pilgrims, English separatists who arrived in America in 1620, held even stricter Puritan beliefs than Cromwell. Consequently, Christmas was not recognized as a holiday in early America. From 1659 to 1681, the celebration of Christmas was actually prohibited in Boston, and individuals displaying Christmas spirit faced fines of five shillings. In contrast, in the Jamestown settlement, Captain John Smith reported that Christmas was embraced by all and passed without incident.

Following the American Revolution, English traditions, including Christmas, fell out of favor. In fact, Christmas wasn’t designated as a federal holiday until June 26, 1870. This marked a significant shift in the recognition of Christmas in the United States, eventually leading to the widespread and diverse celebrations we observe today.

Christmas really the day when Jesus was born?

In the early years of Christianity, Easter held primary significance, with the birth of Jesus not initially celebrated. It wasn’t until the fourth century that church officials decided to establish the birth of Jesus as a holiday. The challenge lay in the absence of a specific date for his birth in the Bible, a point later emphasized by Puritans seeking to dispute the legitimacy of the celebration. While some indications suggested a spring birth (considering the presence of shepherds in the fields), Pope Julius I settled on December 25 as the chosen date. This decision is often associated with the effort to incorporate and assimilate traditions from the pagan Saturnalia festival.

Originally termed the Feast of the Nativity, this custom expanded to Egypt by 432 and reached England by the close of the sixth century. By aligning Christmas with established winter solstice festivities, church leaders aimed to increase its widespread acceptance but relinquished control over how it was celebrated. Over the course of the Middle Ages, Christianity largely supplanted pagan religions.

During Christmas festivities in the medieval period, believers attended church services before engaging in lively, carnival-like celebrations reminiscent of today’s Mardi Gras. Each year, a beggar or student would be crowned the “lord of misrule,” with enthusiastic participants assuming the roles of his subjects. The tradition involved the less fortunate going to the homes of the affluent, demanding the best food and drink. Those who failed to comply faced the likelihood of mischief and pranks. Christmas evolved into a time when the upper classes could, in a sense, repay their perceived societal “debt” by entertaining those less fortunate.

A “Christmas carol“

Around the same period, English author Charles Dickens crafted the timeless holiday tale, A Christmas Carol. The story’s profound message emphasizing the significance of charity and goodwill toward all humankind resonated deeply in both the United States and England. Dickens’ work demonstrated to members of Victorian society the virtues of celebrating the holiday.

During the early 1800s, family dynamics were shifting, becoming less rigid and more attuned to the emotional needs of children. Christmas emerged as a day for families to shower attention and gifts upon their children without fear of being perceived as overly indulgent.

As Americans increasingly embraced Christmas as an ideal family holiday, ancient customs were rediscovered. Observing recent immigrants and attending Catholic and Episcopalian church celebrations provided guidance on how the day should be commemorated. Over the next century, Americans crafted a unique Christmas tradition that incorporated elements from various customs, such as tree decoration, the exchange of holiday cards, and the practice of gift-giving.

While many families believed they were following age-old Christmas traditions, in reality, Americans had reinvented the holiday to meet the cultural needs of a burgeoning nation. The amalgamation of diverse customs contributed to the creation of a distinctly American Christmas celebration.

Who invited Santa Claus?

The legend of Santa Claus traces back to a monk named St. Nicholas, born around A.D. 280 in Turkey. St. Nicholas was known for his philanthropy, having given away his inherited wealth to aid the poor and sick. He traveled the countryside, earning a reputation as the protector of children and sailors.

St. Nicholas found his way into American popular culture in the late 18th century in New York, where Dutch families gathered to commemorate the death anniversary of “Sint Nikolaas” (Dutch for Saint Nicholas), shortened to “Sinter Klaas.” The name “Santa Claus” evolved from this Dutch abbreviation.

In 1822, Episcopal minister Clement Clarke Moore penned a Christmas poem titled “An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas,” more commonly recognized by its opening line: “‘Twas The Night Before Christmas.” This poem portrayed Santa Claus as a cheerful figure flying from home to home on a sled pulled by reindeer to deliver toys.

The enduring image of Santa Claus—a jolly man dressed in red with a white beard, carrying a sack of toys—was solidified in 1881 when political cartoonist Thomas Nast drew inspiration from Moore’s poem. Nast’s depiction of Old Saint Nick became the iconic representation of Santa Claus that persists today.

Christmas Facts

Each year, the United States witnesses the sale of 25-30 million real Christmas trees. There are approximately 15,000 Christmas tree farms in the country, and these trees typically grow for four to 15 years before they are sold.

In the Middle Ages, Christmas celebrations mirrored the lively and festive atmosphere akin to today’s Mardi Gras parties.

- During a unique period in history, from 1659 to 1681, the observance of Christmas was prohibited in Boston, with violators facing fines of five shillings.

- The official recognition of Christmas as a federal holiday in the United States occurred on June 26, 1870.

- The first batch of eggnog made in the United States was enjoyed in Captain John Smith’s Jamestown settlement in 1607.

- Poinsettia plants derive their name from Joel R. Poinsett, an American minister to Mexico who introduced the red-and-green plant to America in 1828.

- Since the 1890s, the Salvation Army has deployed Santa Claus-clad donation collectors into the streets during the Christmas season.

- Rudolph, famously known as “the most famous reindeer of all,” originated from the imagination of Robert L. May in 1939. The copywriter penned a poem about the reindeer as a marketing strategy to attract customers to the Montgomery Ward department store.

- The tradition of erecting the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree was initiated by construction workers in 1931.