Historical Events That Took Place on Christmas

Become the facts on famous historical events that fell on Christmas Day before or Christmas Day.

Apollo 8 orbits the moon, 1968

During the Apollo 8 mission in 1968, astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and William Anders spent Christmas Eve maneuvering around the moon. Originally intended to test the lunar module for the upcoming Apollo 11 moon landing within Earth’s range, the mission plan underwent a significant change when work on the module faced delays. NASA, in an ambitious move, altered the mission to a lunar journey.

Apollo 8 went on to achieve several breakthroughs for manned space flight. The three astronauts became the first humans to escape Earth’s gravitational pull, the first to orbit the moon, the first to witness Earth in its entirety from space, and the first to observe the dark side of the moon. This historic mission marked pivotal advancements in space exploration.

Apollo 8 is perhaps most widely remembered today for the broadcast the three astronauts made when they entered the moon’s orbit on Christmas Eve. As viewers were treated to images of the moon and Earth from lunar orbit, Borman, Lovell, and Anders read the opening lines of the book of Genesis from the Bible. The broadcast concluded with the famous line, “Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you on the good Earth,” growing into one of the most watched television events in history.

World War I Christmas Ceasefire is touched 1914 AD

In the year 1914, the Christmas spirit manifested itself in the most unlikely of places — a World War I battleground. On the evening of December 24, numerous German, British, and French groups in Belgium set aside their weapons and initiated a spontaneous holiday ceasefire. The truce, reportedly instigated by the Germans, saw the decoration of trenches with Christmas trees and candles, accompanied by the singing of carols such as “Silent Night.” British troops responded with their own rendition of “The First Noel,” and eventually, the weary combatants ventured into “no man’s land” — the treacherous, bombed-out space that separated the trenches — to greet one another and shake hands.

According to accounts from the men involved, the soldiers engaged in sharing cigarettes and pulls of whiskey, and some even exchanged Christmas presents with men they had been shooting at only hours before. Taking advantage of the brief lull in combat, Scottish, English, and German troops played a pick-up game of soccer on the frozen battlefield. Not sanctioned by the officers on either side, the truce was an unofficial and spontaneous event. Eventually, the men were called back to their respective trenches to resume fighting, and later attempts at holiday meetings were mostly forbidden. Nevertheless, as the war continued, the “Christmas Truce” would endure as a remarkable example of shared humanity and brotherhood on the battlefield.

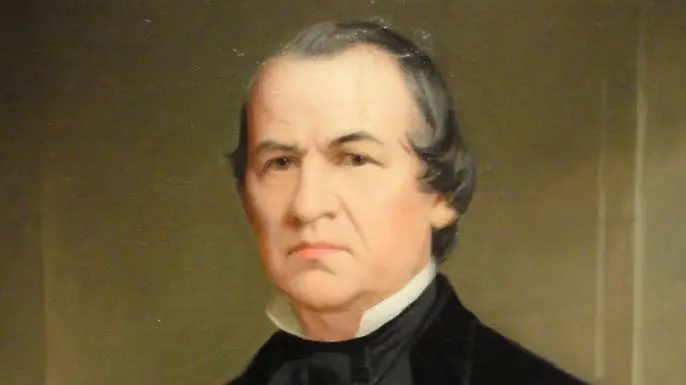

Final pardon to Allied soldiers by President Andrew Johnson 1868AD

During the last days of his term as president, Andrew Johnson presented a notable Christmas gift to a handful of former Confederate rebels. Through Proclamation 179 on December 25, 1868, Johnson issued an amnesty to “all and every person” who had fought against the United States during the Civil War.

This blanket pardon marked the fourth in a series of postwar amnesty orders dating back to May 1865. Previous agreements had restored legal and political rights to Confederate soldiers in exchange for signed oaths of allegiance to the United States. However, these pardons exempted 14 classes of people, including certain officers, government officials, and those with property valued over $20,000. The Christmas pardon served as a final and unconditional act of forgiveness for unreconstructed Southerners, encompassing many former Confederate generals.

The Treaty of Ghent ends the War of 1812

On December 24, 1814, while many in the western world celebrated Christmas Eve, the United States and Great Britain sat down to sign a famous peace agreement ending the War of 1812. Negotiations had commenced in Ghent, Belgium, earlier that August, the same month in which British forces burned the White House and the U.S. Capitol in Washington. After more than four months of debate, the American and British delegations reached a settlement that essentially concluded the war as a draw. All conquered territories were relinquished, and captured soldiers and prisoners were returned to their respective nations.

While the Treaty of Ghent effectively ended the 32-month conflict, it did not take effect in the United States until it was ratified in February 1815. Interestingly, one of the greatest American victories of the war at the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815 occurred more than a week after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed.

George Washington and the Continental Army cross the Delaware River 1776AD

At the end of 1776, the Revolutionary War seemed on the brink of loss for colonial forces. A series of defeats by the British had diminished morale, leading to numerous soldiers deserting the Continental Army. In a desperate bid for a decisive victory, on Christmas Day, General George Washington led 2,400 troops in a daring nighttime crossing of the icy Delaware River. Sneaking into New Jersey, on December 26, the Continental forces executed a surprise attack on Trenton, held by a contingent of German soldiers known as Hessians.

General Washington’s gamble proved successful. Many of the Hessians were still disoriented from the previous night’s holiday revelry, and colonial forces defeated them with minimal bloodshed. Although Washington achieved a surprising victory, his army lacked the resources to hold the city, prompting him to re-cross the Delaware that same day—this time with nearly 1,000 Hessian prisoners in tow. Subsequently, Washington secured successive victories at the Battles of the Assunpink Creek and Princeton. His audacious crossing of the frozen Delaware served as a crucial rallying cry for the beleaguered Continental Army.

William the Conqueror is crowned king of England, 1066AD

In the year 1066, the holiday season played host to an event that permanently altered the course of European history. On Christmas Day, William, Duke of Normandy—more commonly known as William the Conqueror—was crowned king of England at Westminster Abbey in London. This coronation followed William’s legendary invasion of the British Isles, culminating in October 1066 with a triumph over King Harold II at the Battle of Hastings.

William the Conqueror’s 21-year reign witnessed the integration of numerous Norman customs and laws into English life. After consolidating his power by constructing renowned structures such as the Tower of London and Windsor Castle, William also bestowed extensive land grants upon his French-speaking allies. This not only permanently influenced the development of the English language—nearly one-third of modern English is derived from French words—but also contributed to the establishment of the feudal system of government that characterized much of the Middle Ages.

Charlemagne is crowned Holy Roman Emperor, 800AD

Frequently referred to as the “Father of Europe,” Charlemagne was a Frankish warrior king who, in the late 700s, unified much of the continent under the Carolingian Empire. Through extensive military campaigns against the Saxons, Lombards, and Avars, he forged a vast kingdom. Charlemagne, a devout Catholic, zealously converted his subjects to Christianity and implemented stringent religious reforms.

On Christmas Day in the year 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne “emperor of the Romans” during a ceremony at St. Peter’s Basilica. This controversial coronation not only restored the Western Roman Empire in name but also established Charlemagne as the divinely appointed leader of a significant portion of Europe. More notably, it positioned him on equal standing with the Byzantine Empress Irene, who ruled the Eastern Empire in Constantinople. Charlemagne served as emperor for 13 years, and his legal and educational reforms ignited a cultural revival, uniting much of Europe for the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire.