Egyptian Pyramids History

The pyramids, particularly the Great Pyramids of Giza, stand as enduring symbols of Egypt’s opulence and power during ancient times. Constructed amidst Egypt’s status as one of the most influential civilizations globally, these awe-inspiring structures serve as testaments to the paramount role held by the pharaohs in ancient Egyptian society.

Although, pyramid construction spanned from the onset of the Old Kingdom to the conclusion of the Ptolemaic era around the fourth century A.D., the zenith of pyramid building emerged during the late third dynasty and persisted until approximately the sixth (circa 2325 B.C.). Even after more than 4,000 years, the Egyptian pyramids maintain their grandeur, offering a window into the country’s exceptionally rich and illustrious history.

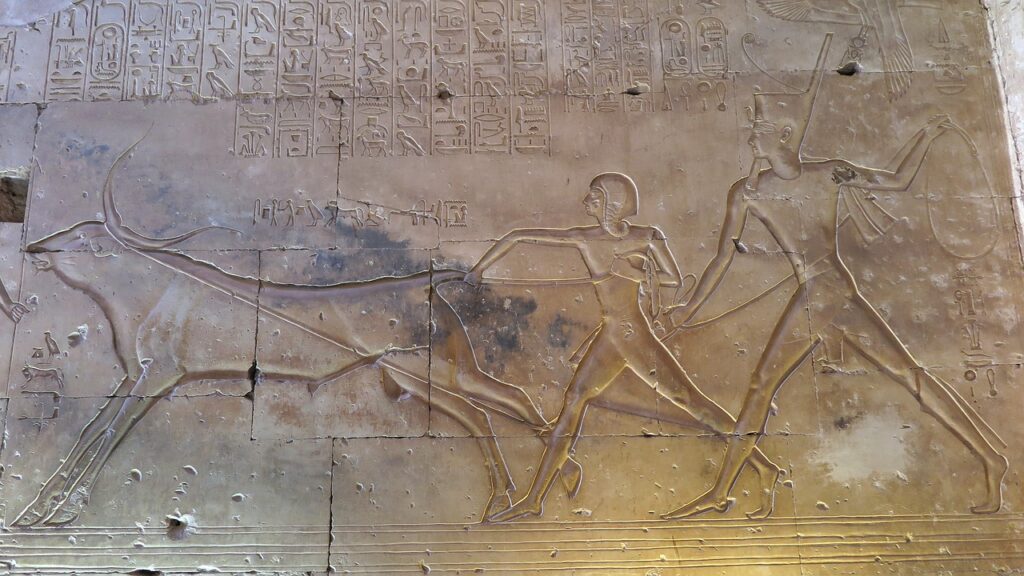

The Pharaoh in Egyptian Society

During Egypt’s prosperous third and fourth dynasties within the Old Kingdom, the nation flourished economically and socially. The position of kings held an unparalleled significance in Egyptian society, residing in a unique realm between humanity and divinity. Believed to be chosen directly by the gods to act as their representatives on earth, the preservation of the king’s majesty posthumously was paramount. After death, the king was thought to transform into Osiris, the god of the afterlife, while the succeeding pharaoh embodied the role of Horus, the falcon-god and protector of Ra, the sun god.

Fascinatingly, the pyramids’ smooth, sloping sides were imbued with symbolism, representing the radiant beams of the sun. This architectural design aimed to facilitate the ascent of the king’s soul to the heavens, uniting with the gods, particularly Ra, the sun god.

Ancient Egyptian beliefs dictated that a part of the king’s essence, known as the “ka,” remained attached to his body after death. The mummification process was crucial to safeguarding this spiritual aspect. All necessities for the afterlife, such as gold vessels, sustenance, furniture, and various offerings, were interred alongside the deceased ruler. The pyramids evolved into the center of a posthumous cult dedicated to the deceased king, ensuring provision not only for him but also for the relatives, officials, and priests interred in proximity to him.

The Early Pyramids

At the onset of the Dynastic Era around 2950 B.C., the tradition of royal tombs began with carved rock structures overlaid by flat-roofed rectangular buildings called “mastabas,” serving as precursors to the eventual pyramids. The oldest pyramid in Egypt, dating back to around 2630 B.C., emerged at Saqqara for King Djoser of the third dynasty. Dubbed the Step Pyramid, it originated as a conventional mastaba but evolved into a significantly more ambitious project. Legend attributes the design to Imhotep, a priest and healer, later deified as the revered patron of scribes and physicians, almost 1,400 years after his time. Djoser’s reign, spanning nearly 20 years, witnessed the assembly of six stepped layers of stone (in contrast to the earlier mud-brick tombs), culminating in a towering structure reaching a height of 204 feet (62 meters). Notably, it stood as the tallest building of its era and was accompanied by a complex of courtyards, temples, and shrines intended for Djoser’s enjoyment in the afterlife.

Following Djoser’s reign, the stepped pyramid became the prevailing style for royal burials, although subsequent endeavors planned by his dynastic successors remained incomplete, likely due to their comparatively shorter reigns. The Red Pyramid at Dahshur, among three burial structures commissioned for Sneferu, the first ruler of the fourth dynasty (2613-2589 B.C.), marked the earliest true pyramid constructed with smooth sides rather than steps. Its name derived from the reddish hue of the limestone blocks forming the pyramid’s core.

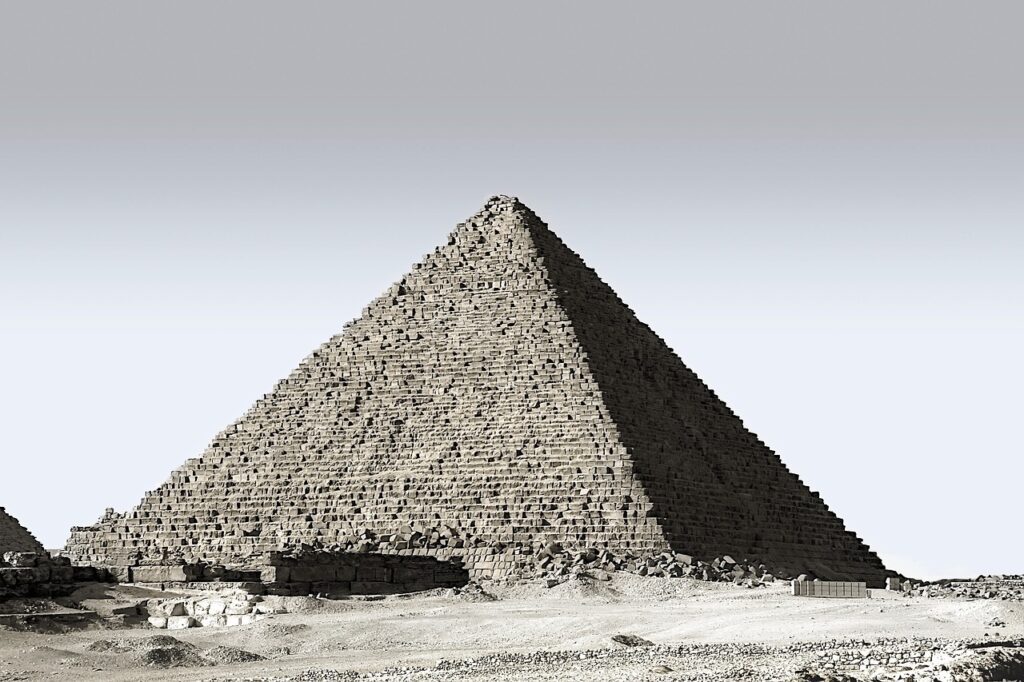

The Great Pyramids of Giza

The Great Pyramids of Giza stand as the most renowned among all pyramids, situated on a plateau along the western banks of the Nile River, at the outskirts of modern-day Cairo. Among these pyramids, the oldest and grandest, known as the Great Pyramid, remains the sole surviving structure of the illustrious Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Commissioned for Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops in Greek), Khufu was the successor of Sneferu and the second ruler of the fourth dynasty. Despite Khufu’s 23-year reign (2589-2566 B.C.), historical records regarding his rule are scarce compared to the grandiosity of his pyramid. Its base sides average 755.75 feet (230 meters), and the original height stood at 481.4 feet (147 meters), solidifying its status as the largest pyramid globally. Adjacent to the Great Pyramid are three smaller ones constructed for Khufu’s queens, while a nearby tomb contained the empty sarcophagus of his mother, Queen Hetepheres. As customary, the surroundings of Khufu’s pyramid feature rows of mastabas, serving as resting places for the king’s relatives or officials to accompany him into the afterlife.

The middle pyramid at Giza was erected for Khufu’s son, Pharaoh Khafre (2558-2532 B.C.). Referred to as the Pyramid of Khafre, it stands as the second tallest pyramid at Giza and houses the tomb of Pharaoh Khafre. Notably, within Khafre’s pyramid complex lies the Great Sphinx, a guardian statue hewn from limestone featuring the head of a man and the body of a lion. This monumental statue, measuring 240 feet in length and 66 feet in height, held the distinction of being the largest statue in the ancient world. By the 18th dynasty (circa 1500 B.C.), the Great Sphinx came to be venerated as the representation of a local incarnation of the god Horus.

The southernmost pyramid at Giza was constructed for Khafre’s son, Menkaure (2532-2503 B.C.). Being the smallest among the three pyramids, standing at a height of 218 feet, it served as a precursor to the smaller pyramids constructed during the subsequent fifth and sixth dynasties.

Who Built Pyramids?

Contrary to some prevailing historical narratives suggesting that slaves or foreign captives built the pyramids, archaeological findings reveal that the labor force likely comprised native Egyptian agricultural workers. These individuals engaged in pyramid construction during the Nile River’s annual flooding, a period when agricultural activities were temporarily halted due to the inundation of nearby lands. Skeletal remains discovered in the vicinity point towards the likelihood of these laborers being indigenous Egyptians.

The colossal task of erecting Khufu’s Great Pyramid involved handling approximately 2.3 million stone blocks, with an average weight of around 2.5 tons per block. These blocks had to be quarried, transported, and meticulously placed to form the pyramid’s structure. Ancient accounts, like that of the Greek historian Herodotus, initially proposed that the construction demanded the effort of 100,000 men over a span of 20 years. However, subsequent archaeological evidence challenges this estimation, suggesting a probable workforce size of approximately 20,000 individuals.

The laborers involved in the construction likely worked in organized groups, employing sophisticated techniques and systems for quarrying and moving the massive stone blocks into position. The logistics and engineering involved in such an endeavor reflect the ingenuity and skill of ancient Egyptian craftsmen and laborers rather than relying solely on forced or enslaved manpower.

The Conclusion of Pyramid Construction Era

The Decline of Pyramid Construction and Royal Authority

Throughout the fifth and sixth dynasties, the construction of pyramids persisted, albeit with a noticeable decline in both their quality and size. Concurrently, the influence and wealth of the reigning kings underwent a decline. Notably, starting with King Unas (2375-2345 B.C.), inscriptions recounting events from the king’s reign began adorning the walls of burial chambers and the interiors of later Old Kingdom pyramids. These inscriptions, known as pyramid texts, represent the earliest significant religious compositions discovered in ancient Egypt.

Pepy II (2278-2184 B.C.), the second ruler of the sixth dynasty, marked the final chapter of the great pyramid builders. Ascending to the throne as a young boy, he held power for an astonishing 94 years. However, during his reign, the prosperity of the Old Kingdom gradually waned. The pharaoh’s once quasi-divine stature diminished as the influence of non-royal administrative officials grew. Pepy II’s pyramid, constructed at Saqqara and completed around 30 years into his reign, stood notably shorter at 172 feet compared to its predecessors from the Old Kingdom era.

Following Pepy II’s demise, the kingdom experienced a dramatic decline, leading to the virtual collapse of the once-strong central government. Egypt entered a tumultuous phase known as the First Intermediate Period. While subsequent kings of the 12th dynasty, during the Middle Kingdom phase, revisited pyramid construction, their efforts never reached the grand scale witnessed during the era of the Great Pyramids.

The Present State of the Pyramids

Throughout ancient and modern history, thieves and vandals have ransacked Egypt’s pyramids, pillaging the tombs of their contents and despoiling their exteriors. Much of the bodies and funeral treasures were looted, and the once-smooth white limestone casings were largely stripped away. Consequently, the Great Pyramids, including Khufu’s, have lost a considerable portion of their original heights, with Khufu’s pyramid now standing at a diminished height of 451 feet.

Nevertheless, these enduring monuments attract millions of visitors annually, drawn by their towering magnificence and the timeless fascination with Egypt’s opulent and illustrious past.